Debt GDP Ratio in India under Modi Government and its implications

Debt GDP Ratio in India under Modi Government and its implications

- Dr. Prem Chand

Internal debt comprises loans raised in the open market, compensation and other bonds, etc. It also includes borrowings through treasury bills including treasury bills issued to State Governments, Commercial Banks and other Investors, as well as non-negotiable, non-interest-bearing rupee securities issued to International Financial Institutions. External debt is the money that a country borrows from a source external to it and has to be repaid in the currency in which it was borrowed after a certain period of time. Most of the time such money is borrowed from foreign institutions like foreign commercial banks and international financial institutions such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF), World Bank, Asian Development Bank (ADB) and also from the governments of foreign nations. Majority of India’s external debt comes from multilateral institutions.

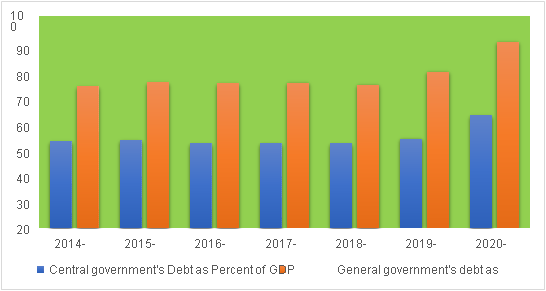

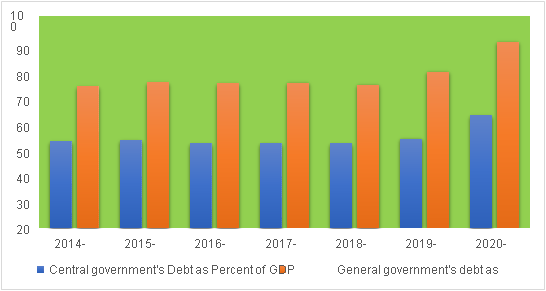

India’s debt burden (internal plus external) as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP) jumped to almost 88 percent for the financial year 2020-21, from almost 74 percent in 2019-20 mainly on account of the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic. The nationwide lockdowns imposed by the government to curb the spread had pushed the Indian economy into a great recession since 1990s crisis with two consecutive quarters of negative growth during year 2020. Since the partial unlock followed by the normal situation over time, the sentiments seemed to be improving, but the country was hit by a second and more severe Covid-19wave which put immense pressure on health and other public infrastructure. Eventually, the government announced various measures as part of its Atmanirbhar package - some extensions of the earlier announced measures while some new ones -which has put huge pressure on its finances, which can be seen from figure1 that general government debt during 2020-21 has almost been 14 percentage higher than the previous year which is highest increase in a fiscal year in last two decades.

Figure-1 Government’s debt in percent of GDP

Source: Status paper on government Debt for 2020-21, Ministry of Finance, Budget Division (GOI)

Now obviously most of us can have doubt about how the government will be able to manage public debt in this fiscal year. If Modi government will not be able to manage then it will negatively affect the growth perspective of India in the long run. The sustainable management of debt will depend on consolidation of gross fiscal deficit of the government which has increased during the Covid-19 pandemic. Furthermore, fiscal consolidation will depend on the GDP growth and tax buoyancy and other macroeconomic management like trade balance, inflation, exchange rate and employment condition of a country.

India's fiscal deficit target for the upcoming fiscal (2022-23) has been set lower than the ongoing financial year. The country’s fiscal deficit settled at 6.9% of the GDP in 2021-22 and has been targeted at 6.4% in the upcoming fiscal. The targeted fiscal deficit is a projected figure which in reality depends on the performance of the economy like GDP growth, tax collections and realization of disinvestment target. Though the GST collections are increasing but still there is a sense of uncertainty whether Modi government will be able to realize the disinvestment target, because in previous fiscal year (2021-22) government achieved only 8 percent of its targeted disinvestment. If it will repeat in the current fiscal, the actual fiscal deficit will be more than the targeted. On the other hand, this will lead to further increase in government’s debt GDP rate.

A Reserve Bank of India occasional paper by Kaur and Mukherjee (2012) pointed out that there is a negative impact of public debt on economic growth at higher levels. They observed that the threshold level of general government debt-GDP ratio for India is 61 per cent, beyond which the debt will adversely affect the growth. This is clear from the figure that during the two consecutive regimes of the present government, the debt GDP ratio has increased which shows the failure of the Modi government in public debt management.

In March 2014, the total debt (internal and external) was Rs. 53.11 lakh crore, whereas in September 2019 the same increased to Rs. 91.01 lakh crore. An increase of 37.9 lakh crore. The debt is increased to around Rs.136 Lakh crores (135,87,893.16 crores) by March 2022. And debt is expected to reach 152 lakh crores by March 2023. From this data it is very clear that the net debt of India is increasing continuously at very high rate. In spite of this increasing debt, Indian economy is not doing well upon many social and economic indicators. As a result of which our Debt to GDP ratio is rising and growth is not happening.

The fiscal consolidation also depends on the growth of a country. During the Covid-19 outbreak, the growth rate was negative almost -8 percent in 20-21. Though the Covid-19 pandemic has led country’s growth to negative, however the slowdown of the economy was started before the outbreak of the pandemic during the normal period itself. Slowdown had started in 2018 in Indian economy because of two naïve policies: ‘Demonetization and the GST’ – which had devastating impact on demand-side economy and led to the great slowdown of economy. When the country was passing through demand-led slowdown, the sudden outbreak of Covid-19 pandemic further aggravated the slowdown in India which led to the lowest growth in India among developing nations across the world. Under the umbrella of pandemic, the Modi government justified the low growth rate which had actually started quite before the pandemic, because of mismanagement of economy from demand side.

The Modi government is only emphasizing supply-side factor of growth which will not be sustainable for long time. For growth to be inclusive and sustainable, the government must focus on reducing inequality, poverty, inflation and generating more employment which determine the aggregate demand and growth of economy. If we talk about the data from World Bank, Since the 2000s, India has made remarkable progress in reducing absolute poverty. Between 2011 and 2015, more than 90 million people were lifted out of extreme poverty. But, during COVID-19 pandemic many people reached the level of below poverty line.

According to ‘Oxfam Report’ 2021, the collective wealth of India’s 100 richest people hit a record high of Rs. 57.3 lakh crore (USD 775 billion). However, the share of the bottom 50 percent of the population in national wealth was a mere 6 per cent. Further, the report says that during the pandemic (since March 2020, to November 30, 2021), the wealth of Indian billionaires increased from Rs. 23.14 lakh crore (USD 313 billion) to Rs. 53.16 lakh crore (USD 719 billion). On the other hand, more than 4.6 crore Indians are estimated to have fallen into extreme poverty in 2020, nearly half of the global new poor according to the United Nations. Unemployment has touched its historical high during the present government’s regime. It was 3 percent during 2011-12 and is almost double now (5.6 percent) and unfortunately the unemployment rate among youth is double than national average.

Inflation rate is on historic high. WPI and CPI is more than 14 and 6 percent respectively which will further hamper the Acche Din of common man in general and economic growth in particular. On the other hand, fuel (Petrol, Diesel and CNG) prices are skyrocketing which further will spill over on inflation and growth of the economy.

In spite of this increasing debt and high Debt to GDP ratio, Indian economy is not doing well upon many social and economic indicators. This raises a very important question - where is this money going? Who are the beneficiaries of such borrowing? These low socio-economic indicators also raise an important question upon the way government is spending this money. In brief, all the economic indicators reveal that the present government is not paying focus on the long-run sustainable growth and is rather busy with achieving their election goal by pleasing electoral through announcement and meager transfers. Government needs to focus upon creating more jobs rather than reducing jobs in public sectors. For growth to be sustained in long-run and for the development of country like India, we need to focus on reducing inequality, poverty, unemployment and inflation. All these indicators are currently at their peak in India.

The author is an Assistant Professor in ARSD College (University of Delhi) Former President NSUI JNU, Former Joint Secretary, DUTA