Unemployment Crisis - Where are the Jobs?

In the run-up to the 2014 general elections, then PM candidate Narendra Modi made tall promises to create jobs for every job seeker – a total of two crore jobs a year. These promises were quickly forgotten after PM Modi assumed power. Thereafter, demonetisation and a hastily implemented and flawed Goods and Services Tax (GST) regime wrecked the economy. India’s youth, who were concerned about job-less growth now had to face job-loss growth, as the economy’s growth momentum reversed, and employment shrank.

In 2017-18, the National Sample Survey Office (NSSO) approved a report based on the Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS) which showed that India’s unemployment rate had touched a 45-year high of 6.1%. The government’s response was to withhold its official survey (leading to the resignation of two members of the National Statistical Commission). This attitude of denial and deception has been the government’s strategy to deal with the unemployment crisis, (and indeed with findings that show the government’s performance in a bad light).

As a result, unemployment remains unreasonably high. When the COVID-19 pandemic raged, the sudden, ill planned lockdown enforced by the Modi government had the effect of turning job losses into massive job destruction. The impact was visibly felt by migrant workers who were forced to walk hundreds of kilometres to their native villages, where they added to India’s already underemployed agricultural workforce.

Despite the Modi government’s attempts to deny the severity of the unemployment crisis, a closer examination of Indian labour markets points to signs of deep distress. The government’s own employment data unveils a troubling dimension: the deteriorating quality of jobs, a crisis of youth unemployment, the surge in informal labour, and stagnant real wages.

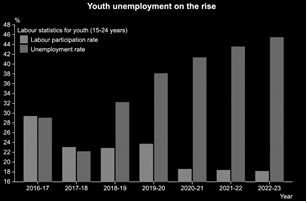

Youth Unemployment Rate at 45.4%, Every Second Young Person is Jobless

The second term of the Modi government was characterised by high levels of unemployment, particularly among the youth. This has been one of its biggest challenges. Despite the government’s assertions of declining unemployment, data from the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE) showed that in FY 2022-23, youth unemployment reached 45.4%, i.e., practically every second young person was jobless.

Figure 1.1 Source: Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy

Figure 1.1 Source: Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy

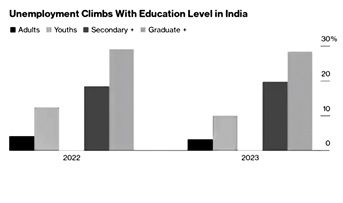

The problem is accentuated by the fact that education is actually diminishing the job prospects of youth, thus belying the hopes of families who have invested their scarce resources in sending their children to college. This may be caused by factors such as the diminishing quality of education and a mismatch between what is taught in the classroom versus what is needed in the market. A study by the International Labour Organisation reported that graduates had an unemployment rate of 29.1%.

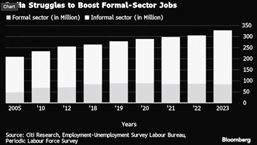

Figure 1.2 Source: Bloomberg

Figure 1.2 Source: Bloomberg

India’s Stagnating Labour Force and the Impact on Women

The labour force participation rate (LFPR) trends from 2011-12 to 2022-23 indicate stagnant employment growth and ongoing gender and regional disparities. The male labour force participation rate in both rural and urban areas has remained stagnant. Female labour force participation rates exhibit more significant fluctuations and lower overall levels of participation. The rural female labour force participation rate experienced a sharp decline in the years prior to the pandemic before rising to 41.7% in 2023-24.

Considering the backdrop of the pandemic, economists argue that the large-scale entry of rural women into the workforce indicates signs of rural distress, as women were compelled by economic distress to seek employment. Further, large numbers of women are working in unpaid, care-related jobs or on family agricultural holdings. In comparison, the urban female labour force participation rate, has remained consistently lower than for rural females, and has only shown a modest upward trend from 2019-20 onwards.

While more women are part of the workforce, very few have access to regular salaried jobs. In 2017-18, every fifth job a woman held was salaried. The job destruction in a slowing economy has meant that now less than 16% jobs held are regular and a majority of the workforce is self-employed.

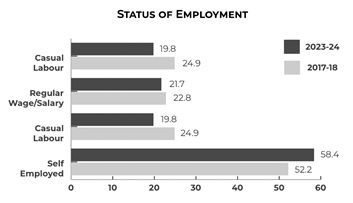

Figure 1.3 Source: Business Standard

Figure 1.3 Source: Business Standard

Quality of Jobs: Rise of Informal Labour

In the absence of robust good quality job creation, there has been a sharp rise in the proportion of self-employed individuals within the workforce. Currently, over half of men (53.6%) and more than two-thirds of women (67.4%) are categorised as ‘self-employed’.

The share of regular wage workers has fallen while there has been a rise in those self-employed. Ideally, with economic growth, however moderate, more salaried jobs should have been created.

A 2024 report by Citigroup India indicates that at the current growth rate, India will fall short of creating the 12 million jobs yearly which are necessary to accommodate new entrants into the labour market. The report also underscores challenges related to job informality and quality, noting a decline in formal sector employment compared to pre pandemic levels.

Figure 1.4 Source: Periodic Labour Force Survey 2017-18 and 2023-24

Figure 1.4 Source: Periodic Labour Force Survey 2017-18 and 2023-24

Figure 1.5 Source: Business Standard

Figure 1.5 Source: Business Standard

Reversal of Structural Transformation: Decline of the Manufacturing Sector

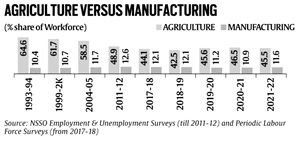

During the UPA years, there were concerted efforts to reduce dependency on agriculture and focus on the manufacturing and service sectors. Between 2004-05 and 2011-12, the percentage of workers engaged in agriculture declined from 58.5% to 48.9%, while the number of workers in manufacturing increased, reaching its peak at 12.6% in 2011-12.

However, since 2015-16 there has been a decline in jobs in the manufacturing sector while the post pandemic period has seen a steady rise in agricultural jobs, leading to a reversal of the structural transformation that the economy witnessed between 2004 and 2012.

Since 2018-19, the percentage of workers engaged in agriculture has increased from 42.5% to 46.1% in 2023-24. At the same time, workers engaged in the manufacturing sector have declined from 12.1% to 11.4%. This growth in agricultural jobs is counter to the universal pattern followed by economies as they develop.

Manufacturing has gone from being the sector with the second largest employment in 2017-18 to the fourth largest in 2023-24. Unlike other countries where the growth process has been manufacturing-led, India’s growth has been driven by the services sector. The International Labour Organisation’s India Employment Report 2024 describes India’s structural transformation as “stunted.”

Figure 1.6 Source: Indian Express

Figure 1.6 Source: Indian Express

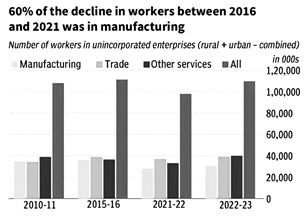

Shrinking MSME/Informal Sector Employment

Successive economic shocks over the decade – demonetisation, a hasty, flawed GST in 2017, and an unplanned COVID-19 lockdown have adversely affected the informal sector. These disruptions have collectively strained small businesses, resulting in a significant decline in both the number of operational enterprises and the employment they generate. Stringent compliance requirements and other policies of the government have pushed informal entities to shut down.

Analysis of the latest Annual Survey of Unincorporated Enterprises shows that between 2016 and 2021, the number of workers in the informal sector declined by 1.3 crore. In the informal sector, 24 lakh enterprises shut down between 2015-16 and 2021-22 and manufacturing employment reduced by 81 lakhs.

Figure 1.7 Source: Business Line

Figure 1.7 Source: Business Line

Vacancies in Government Jobs, 3 Jobs per 1000 Applicants

Figure 1.8 Source: Outlook Business

Figure 1.8 Source: Outlook Business

Underemployment

A paper by the Ministry of Statistics in May 2024 finds that India is grappling with the issue of high underemployment. Many individuals, particularly the youth, are employed in positions that do not match their skill sets, leading to lower wages and job dissatisfaction. A report by the International Labour Organisation (ILO) highlights that the pandemic exacerbated these issues, with many taking lower-paying jobs or facing informal and insecure employment arrangements. The lack of adequate job creation, particularly in non-farm sectors, and the mismatch between skills and available jobs, highlights the need for structural changes in India’s labour market to address the issue of youth underemployment.

The Government’s Claims of Job Creation

The government has taken to using the KLEMS database of the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) to claim that substantial job creation is taking place. However, economists regard the KLEMS database as unreliable as it also includes the informal economy. The government’s own PLFS showed that self-employment has increased to 58.4% in 2023-24 from 52.2% in 2017-18, and the percentage of workers who had regular wages had dropped to 21.7% in 2023-24 from 22.8% in 2017-18.” Former Chief Statistician of India, Pronab Sen, points out: “The data shows increase in self-employment activities, which means that people are working to survive in absence of new jobs. It is incorrect to say that these are all additional jobs created in the economy.”

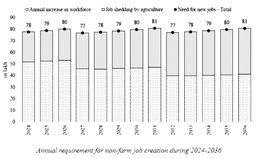

Figure 1.9 Source: Economic Survey 2023-24

Figure 1.9 Source: Economic Survey 2023-24

Indeed, the government’s own Economic Survey released in July 2024 contradicts the claim of substantial job creation by pointing out that the “Indian economy needs to generate an average of nearly 78.5 lakh jobs annually until 2030 in the non-farm sector to cater to the rising workforce.” The Economic Survey also refers to a NITI Aayog study that shows that the “gig economy” created 77 lakh jobs in 2021-22 and is expected to employ 2.35 crore by 2029-30, or 6.7% of India’s non agricultural workforce. In this context, it is important to heed the ILO’s warning that “gig jobs” are essentially temporary jobs which blur the distinction between formal jobs and self-employment and raise questions about workers’ working conditions.

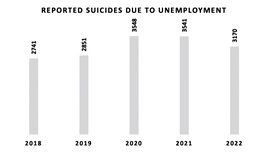

Suicides Due to Unemployment

Ultimately, it is important to note that the unemployment crisis has also resulted in tragic consequences. According to the Accidental Deaths and Suicides Reports, between 2018 and 2022, a total of 15,851 individuals died by suicide due to unemployment.

Figure 1.10 Source: Accidental Deaths and Suicides Reports 2018-22

Figure 1.10 Source: Accidental Deaths and Suicides Reports 2018-22

Extracts from the booklet published on ‘What happened to Growth’ under the leadership of Prof. M.V. Rajeev Gowda, AICC Research Department