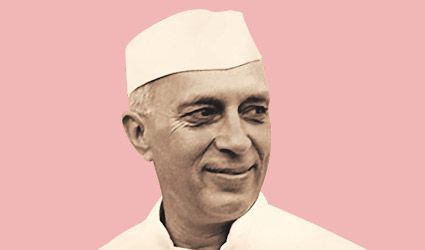

Jawaharlal Nehru: The Human Face

- Capt. Praveen Davar

Soon after joining as Chief Security Officer to Prime Minister Nehru in August 1952, I accompanied him to Kashmir. He was 63 years of age but seemed to be 33 if his energy levels were to be considered. He was fair, handsome and striking. He rode horses harder than any of us. He walked like a young man, could swim like a champion and always ran up a flight of stairs. He worked sixteen hours a day, regularly day after day.

(Rustamji’s diaries)

Much has been written, and will continue to be written for centuries to come, on the life and the gigantic contribution of India’s first and longest serving Prime Minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, the Architect of Modern India. This essay, is primarily based on the diaries of KF Rustamji, the security officer of Pt. Nehru (1952 -58) compiled by another IPS officer PV Rajgopal in ‘I was Nehru’s shadow’, a book published in 2014. It covers the little known human, and humane, side of India’s most popular and charismatic Prime Minister.

Rustamji took over as the Chief Security Officer to the Prime Minister in August 1952. His first entry records what is quoted above followed by: ‘He had a frugal lifestyle and his eating habits were simple. JN’s simplicity in his dress is well-known. His usual dress was the churidar and white achkan with a red rose in the buttonhole... The cap - white and faintly worn, gave him a handsome, youthful appearance while successfully concealing his bald pate... Half the people of India would not have recognized Nehru if they had seen him without the cap.’

Jawaharlal Nehru disliked wastage. ‘He cribbed and nagged about food wastage, stopped the car often, so that someone might go and turn off a leaking tap.’ In September 1956, Rustamji accompanied Nehru to Riyadh and writes: ‘I found him padding around the fabulous palace specially built for his visit, switching off the lights that were blazing all around ... trying to economise in an Arabian Night’s palace.’ During the PM’s visit to Dibrugarh (Assam) the same year Rustamji records: ‘I entered his room before dinner and saw something which interested me - the black socks of the Prime Minister which had been clumsily darned in white thread by Hari (Nehru’s personal attendant). Thereafter, I often saw Hari stitching his torn socks. The same pair of shoes went on for years.’ Rustamji rightly observes, ‘I doubt whether there is any head of state who lived more simply and endured as much as Nehru.’ This was because Jawaharlal had taken to simplicity early in life despite the fact he had been brought up in the luxury of Anand Bhavan that was built by his doting father, Motilal Nehru who was amongst the top most successful lawyers in the country. In his book Nice Guys Finish Second, the author BK Nehru (nephew of Jawaharlal Nehru) has written: ‘Much to Motilal’s chagrin and disappointment, Jawaharlal took no interest whatsoever in the new house. Infact, he was positively non - cooperative to show his disapproval of his father’s continued preoccupation with the material world. A contractor who suggested that Dadaji (Motilal) might consult the man for whom the house was being built was snubbed by being told that the ‘Chhote Saheb’ had no interest whatever in the house... Father and son both wore khadder; but while the father wore the finest, brought specially from Andhra, the son wore the coarsest because that was all the peasant could afford. Later, Motilal Nehru (twice President INC) himself gave up his luxuries and lucrative profession, and donated the palatial Anand Bhavan for the cause of Freedom Struggle.

Nehru wanted food served to him to be simple. He disliked rich and spicy food. Once he caught cold and when his daughter Indira (later PM Indira Gandhi) asked him how his cold was, he replied that it was the rich food they had started serving in Rashtrapati Bhavan that upset him. ‘I don’t mind the work, which naturally is heavy, when the foreign visitors arrive, but I can’t stand the feasting part of it.’ There were few things he hated more than a formal banquet and expressed his displeasure whenever he saw elaborate arrangements being made in state guest houses for his visits. ‘There is no reason at all why all these cooks and crockery should come from elsewhere’, he remarked at a wayside guest house in Mysore.

Though he strongly believed in, and infact encouraged, a healthy opposition what ‘ annoyed JN most of all, apart from ‘stupid opposition’, was vulgarity. He hated anything that smacked of a low, mean mind. Ostentation and pomp, a loud voice, formal sit down dinners, feasting and cocktail parties, fanaticism and orthodoxy- all repulsed him...there was no guile or trickery in his thinking, no desire to harm anyone... his mind was open and harmless. He spoke of progress for a just and free democracy...all he wanted to do was to improve the world and make it a better and safer place to live in.’

The Prime Minister enjoyed long road journeys and was usually cheerful and relaxed then. But once in Rayalaseema region, reeling under severe drought, he travelled 219 miles (353 kms) at the end of which he was obviously tired, but not more than his 27 years younger security officer who asked him to curtail his programme of next day. This is what Nehru replied: ‘We should not alter a programme that has once been fixed because it would cause inconvenience to so many people. Besides, it’s not impossible for me ...though I may lose my temper more often. ‘Later in a speech in Madras (now Chennai) the PM said he wanted to devote every ounce of his energy he possessed to the growth of his country before he was thrown on the scrap heap of history. ‘JN had an indefatigable energy to work. He began his work at about 8 o’ clock in the morning, dictating to a relay of secretaries. Then he came to the office, met a lot of people, went back for lunch, came again and usually went on to work till about 12 or one o’clock at night. On tours his energy was inexhaustible.’ If he worked 16 hours daily on a routine day, on tours it could stretch upto 18, or even 20 hrs. As Prime Minister (1984 -89) Rajiv Gandhi perhaps inherited this trait of his grandfather to which I was a personal witness during an election campaign in the Northeast in 1987/8.

In a separate chapter entitled ‘Nehru’s Courage’, Rustamji narrates many incidents relating to accidents of Nehru’s cars and aircraft, and the Prime Minister escaping death by a whisker. Due to space constraints one such incident will suffice to exemplify Nehru’s personal courage. On February26, 1957, the PM took off from Mangalore in an Ilyushin aircraft presented by Soviet (now Russia+) Prime Minister Bulganin. Somewhere midair one of the twin engines of the plane caught fire, and every passenger, including the crew, were naturally in a state of panic. But Nehru was absolutely calm. ‘What is JN thinking about?’, wondered Rustamji. He was happily chatting with BR Vats, the PTI correspondent on board. Though the fire was extinguished, the extremely worried Rustamji kept his thoughts to himself: ‘If the fire has not been completely extinguished, it may reach the fuel tank and then the plane will explode. We wouldn’t even feel it. But what about those we leave behind? ‘The Chief security officer, thinking that death was imminent, even wrote a touching farewell note to his wife: ‘My last thoughts will be of you and Kerman... forgive me for all my faults.’ Rustamji had begun this chapter with the words: ‘Among the many facets of JN’s character worthy of delineation, the one I admired most was his undoubted personal courage. Nehru was not a man who was afraid of death.. He could stare death in the face without the slightest sign of nervousness. In moments of danger, he withdrew into himself and supported all who were around him with his calm courage. ‘

In early 1954, Lal Bahadur Shastri, then Railways Minister, made efforts to persuade JN to have a bath in the Ganga on the occasion of Kumbh Mela. Shastri argued: ‘It is a custom followed by millions of people. You should do it, if only out of respect for this faith and love of Ganga. The PM replied: ‘It is true, the Ganga means much to me. I see on its waters the story of India... the Ganga is part of my life, and the lives of millions of people of India...To me it is the river of history ...I enjoy bathing in it otherwise- but not during the Kumbh.’ Nehru was religious sans rituals. What did he believe in? Rustamji notes: ‘His views were closest to Buddhism… but I am not sure. They were closest to the purest form of Hinduism- tolerance, compassion, faith in mankind and distrust of dogma.’ Concluding a chapter ‘Nehru- The Man’ Rustamji writes: ‘I have a feeling that we will not see the likes of him for years to come. He was the real genius of India compounded of Buddha, Gandhi and a Western scientist of note, like Albert Einstein.’ Indeed the like of Jawaharlal Nehru may not be born for centuries to come. As Alma Iqbal wrote: Hazaro Sal Nargis Apni Benoori Pe Rotee Hai, Badi Mushkil Se Chaman Mein Hota Hai Deedawar Paida .

The writer is Editor, The Secular Saviour and a former Secretary AICC)