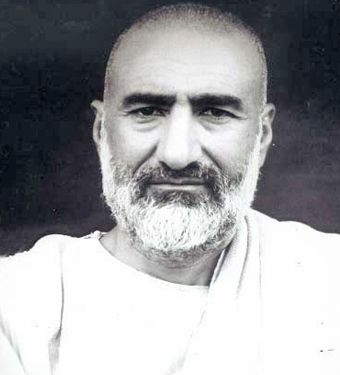

Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan: Transparent Purity and Ascetic Severity, Moments to behold

- Aditya Krishna

The India of 2021 is very different from what its towering freedom fighter Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan envisioned. The last decade has seen a rise in majoritarianism and violence, the two things Badshah Khan opposed all his life. So, an important question all the progressive Indians who believe in democracy and pluralism should ask is what Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan can offer us, in 2021, to fight the most important challenge since our independence.

According to me, Indians can learn four very important lessons from the man who originally hailed from Utmanzi but was and is respected from Kashmir to Kanyakumari.

The first is ‘Courage’ or ‘himmat’.

When Mahatma Gandhi arrived at the political scene in India, he was like a ‘fresh air,’ as Jawaharlal Nehru had approximately put. He taught Indians ‘not to fear’. Perhaps we have become fearful again in 2021, when politicians, journalists, activists, teachers, students, officers and judges are not standing up for their compatriots. We have become fearful because the government arrests individuals on absolutely frivolous charges and in custody, many are denied civil liberties. The judiciary has also not responded on time on the bail petitions.

The life of Badshah Khan teaches us not to be afraid of jails. He had spent more than a quarter century in inhospitable conditions in prisons during his lifetime. He once recalled about his experience in Peshawar Jail as such: “The cell was stinking, the earthen sanitary part was full to the brim with faeces. I stepped out of the cell and told the officer that the stink was unbearable. He pushed me inside and locked the door.”

In another instance, talking about the ugly condition of food in jail, he said to one of the officers, ‘I put this before a cat but it would not touch it, and you give this to human beings’.

The pride in the ‘Pathan’ was such that he remained unwavered to his principles.

His punishment could have been reduced if he would have sought mercy, but he chose not to. He was also not prepared to take even the slightest benefit in jail. Once, he declined food and milk which was offered to him by a Muslim jailor.

Those 27 years of incarceration can be an inspiration for all these current-day student leaders, activists and journalists who are languishing in jail and fighting the government. The second thing that was instrumental to Ghaffar Khan was non-violence (‘ahimsa’ or ‘adamtashadud’). Protesters, students, journalists, farmers, and the brave women of Shaheen Bagh have been fighting this government non-violently.

Post-2019, India saw two major protests, one against the Citizenship Amendment Act and the other ongoing protest against the three Farm Bills. In both the cases, protesters adhered to the method of ‘ahimsa’ taught to us by people like Mahatma Gandhi, Dr B.R Ambedkar, and Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan. We understood that it’s far more difficult for any government to crush non-violent protests. However, a distinction also needs to be made—and this is where Badshah Khan’s life comes into picture. ‘Adam tashadud’ is not only a way of protest but more importantly a way of life.

Traditionally, coming from a place in Utmanzi, and from a community of Pakhtuns, which many times stereotypically is linked with rowdyism, Badshah Khan showed the world that a non-violent Pakhtun is more dangerous than a violent one. He once stated, ‘Britishers crushed the violent movement in no time, but the non-violent movement, in spite of intense repression flourished’... Also, it won the ‘love and sympathy’ of the masses in the Frontier Province, which wouldn’t have happened in a violent movement because when a British culprit was killed or punished violently, the whole village had to suffer extreme subjugation and repression from the Britishers.

Another remarkable contribution was tracing the philosophy of non-violence from Islam. It was similar to what Mahatma Gandhi did with Hinduism.

Badshah Khan had promulgated that he had learnt non-violence, which generated love and made individuals bold, from Prophet Muhammad. In a gathering at Bardoli, he said, ‘There is nothing surprising in Musalman or Pathan like me subscribing to non-violence. It is not a new creed. It was followed fourteen hundred years ago by the Prophet, all the time he was in Mecca....But we had so far forgotten it that when Mahatma Gandhi placed it before us we thought he was sponsoring a new creed or a novel weapon.

Today, patriotic and dissenting Indians in general can learn ‘ahimsa’ from Badshah Khan, which he considered ‘the mightiest weapon in the world’. The theocratic interpretation of non-violence can appeal to India’s Muslims who are dissenting against the oppressive government who is trying all its means to curtail the liberties of the largest minority in India.

The life of Mahatma Gandhi and Ghaffar Khan is synonymous with interfaith harmony. Like Gandhi, Badshah Khan too was fully committed to Hindu–Muslim–Sikh–Christian–Jain–Parsi–Buddhist unity in the subcontinent. It is also remarkable that generally, among the ‘liberal intelligencia,’ there is some belief that people who are irreligious, agnostic, and atheists are mostly secular, but in the subcontinent, Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan, Mahatma Gandhi, Maulana Abul Kalam Azad, and Chakravarty Rajgopalachari’s lives tell us that they used religion to fight what they considered irreligious.

Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan understood that for a prosperous subcontinent, unity between Hindus and Muslims is fundamental. How Hindu–Muslim unity and his utmost surrender to God would go hand-in-hand is best described by Mahadev Desai, the secretary of Mahatma Gandhi. “I have the privilege of having a number of Muslim friends, true as steel and ready to sacrifice their all for Hindu-Muslim Unity, but I do not yet know one who is greater than or even equal to Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan in the transparent purity and the ascetic severity of his life, combined with extreme tenderness and living faith in God”.

After the formation of Pakistan, Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan remained committed to interfaith harmony and protection of minorities. When he was invited by the founder of Pakistan, Muhammad Ali Jinnah, to join the Muslim league, Ghaffar Khan refused by stating that he could not join a party whose members had recently looted the properties of Pakistani minorities—Hindus and Sikhs.

He returned to India after a gap of 22 years in 1969, the year that saw the centenary celebrations of Mahatma Gandhi. The year also saw communal violence in many pockets of India. Badshah Khan held a fast for peace in Ahmedabad and then later in Delhi. On 18 October, 1969, he said to the majority community, which is also very poignant in today’s context, ‘Hindus only work in Hindus areas... Get close to the Muslims. Don’t think of them as outsider’.

Can ‘New India’ heed to the advice of Ghaffar Khan? Perhaps time will tell.

The fourth value Indians can garner from him is building solidarity with other communities.

As a Muslim, he always stood with minorities of Pakistan, Hindus, Sikhs, Christians, Parsis, etc. He worked for the betterment of communities which were historically discriminated—Dalits, tribals and women.

Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan campaigned strongly against untouchability along with Mahatma Gandhi. He also worked for their betterment and opposed the inhumane practices in the strongest possible words. When he stayed with sweepers at Shimla, he came to know how deplorable their conditions were. He wrote to Gandhi that ‘their quarters were not fit for animals much less for human being.’ He was keen on uniting all communities, because he was aware that real freedom can only flourish in India on the basis of amity and cooperation.

For most parts during the British rule, he and his brother were not allowed to interact with the tribals. Badshah Khan considered tribals of the province his ‘kith and kin’ and believed they should be won by ‘love and not by force’. In a speech he had said, “I want to organise primary schools, civil dispensaries, centres for training technical hand for cottage industries among tribesmen. If the political Department honestly cooperates with me, I can promise big results in five years time. Love can succeed where Bombs have failed.... I want to work for their prosperity.”

The question of freedom of womenfolk also surrounded Badshah Khan. He opened a school for girls as he knew education is the strongest path to liberate women. He sent his daughter Mehr Taj in her teens to study in England. In 1931, when Jawaharlal Nehru, who was then General secretary of Congress, wanted to help Peshawar Congress Committee, the self-respected Pakhtun leader declined the offer by saying ‘You carry your load, we shall bear ours’. However, he was willing to take his help for the betterment of women and said, ‘If you want to help us then build a girls’ school and a hospital for women’.

He was always wary of many conservative practices. May, the second wife of Dr. Khan Sahib (Badshah Khan’s elder brother), describes Ghaffar Khan as similar to ‘Christ’. A conversation with Gandhi also reveals how non-interfering a man he was at home. When Gandhi asked him if his brother’s second wife was converted to Islam, Badshah Khan replied, ‘You will be surprised to know that I cannot say whether she is a Muslim or a Christian’. He knew that faith is a personal choice and his next statement to Gandhiji is surely a lesson for 2021 India, especially in the midst of our new ‘Love Jihad Laws’. ‘She was never converted... that much I know. And she is at complete liberty to follow her faith...I have never so much asked her about it’.

He started a journal ‘Pakhtun,’ which, apart from raising the politico-cultural issues of Pakhtuns, was critical of patriarchal practices followed by his people. In one of the pieces written by ‘Nagina’ (a woman from Pakhtun) that advocated for freedom for women, it had an excerpt which read, ‘Except for the Pakhtun, the women have no enemy. He is clever but ardent in suppressing women. Our hands, feet and brains are kept in a state of coma.

O Pakhtun, when you demand your freedom, why do you deny it to women’.

Ghaffar Khan was a very strong advocate of women participating in the Freedom Struggle. In a meeting organised by women in 1931 he said, “Whenever I went to India and saw the national awakening and participation of the Hindu and the Parsi women, I used to say to myself, would such a time come when our Pakhtun women would also awake? ...Thank God today I see my desires fulfilled. In the Holy Qur’an you have an equal share with men. You are today oppressed because we men have ignored the commands of God and the Prophet. Today we are the followers of custom and we oppress you...”

Today, when Dalit, Adivasi and Feminist Movements need allies, a look into Badshah Khan’s life can be helpful for the intellectuals who address this question. A true tribute to him will be working towards an egalitarian society and accepting its plurality. In 2021, we can take the same oath which he, Dr. Khan Sahib, and their KhudaiKhidmatgars used to take:

“I am a Khudai Khidmatgar, and as God needs no service I shall serve Him by serving His creatures selflessly. I shall never use violence, I shall not retaliate or take revenge, and I shall forgive anyone who indulges in oppression and excesses against me.... I shall give up evil customs and practices. I shall except no reward for my services, I shall be fearless and be prepared for any sacrifice”.