Motilal Nehru’s Contribution in making of the Constitution

- Capt. Praveen Davar

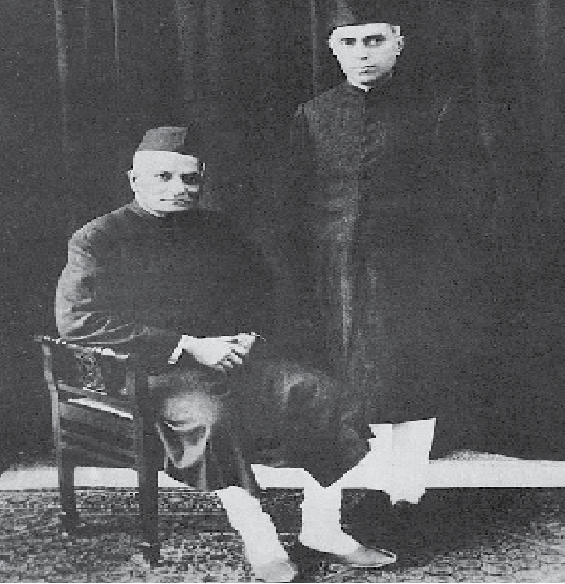

The 161st birth anniversary of Pandit Motilal Nehru, twice President of the Indian National Congress (INC) 1919, 1928 fell on May 6, 2022. Motilal Nehru was a great parliamentarian, a gifted orator and a brilliant lawyer who gave up his lucrative legal profession and, later, his palatial house in Allahabad Anand Bhavan for the cause of the freedom struggle. Much has been written in these columns, earlier, of Motilal Nehru’s gigantic contribution in the Gandhi-led independence movement. This essay will be restricted to the ‘Swaraj Constitution’ prepared by Motilal Nehru that carried his name and is an important archival material famously called the ‘Nehru Report’.

The Madras Session of INC, held in December 1927, had directed the Congress Working Committee to draft a ‘Swaraj’ Constitution in consultation with other parties. In February, 1928, an All-Parties Conference met in Delhi with Dr. Ansari, the Congress President, in the chair, and voted for ‘full responsible government’. At its Bombay meeting in May, it appointed a sub-committee to determine the principle of the Indian constitution. The sub-committee was presided over by Motilal and included Sir Ali Imam and Shuaib Qureshi (Muslim), Aney and Jayakar (Hindu Mahasabha), Mangal Singh (The Sikh League), TejBhadurSapru (Liberals), N.M. Joshi (Labour), G.R. Pradhan (Non-Brahmins). Jawaharlal Nehru, who was then the General Secretary of the AICC, also acted as the General Secretary of the Constitution making Committee, which came to be known as the Nehru Committee.

The Nehru Committee had to find an answer to the sinister question which was to shadow Indian politics for the next twenty years: the position of the minorities, and especially of the Muslim minority, in a free and democratic India. If British autocracy was to be replaced by an Indian democracy, would it give a permanent advantage to the Hindus, who heavily outnumbered the Muslims? Was it, as Sir Syed Ahmed had put it, a game of dice in which one man had four dice, and the other only one? Two of the principal items in the Muslim demand were that the form of the Constitution of India should be federal and that the Legislatures and other elected bodies should be constituted on the definite principle of adequate and effective representation of minorities in every province; without reducing the majority in any province to a minority or even equality.

The joint action of the Congress, the All-India Muslim League and the other organizations in the beginning of 1928in drafting a Constitution for India was the result of the humiliation heaped on Indians by the appointment of the ‘All-white’ Simon Commission and a challenge thrown out by the Secretary of State Lord Birkenhead to India - to produce a Constitution acceptable to all. The All-Parties Conference proceeded with the work of Constitution-framing and after doing a substantial part of it left it to the Nehru Committee. It was discussed and adopted with modifications at a meeting of the All-Parties conference at Lucknow and was ultimately placed before an All-Parties Convention held in Calcutta in the last week of December 1928. Other forces had been working in the meantime and differences had arisen with the representatives of the All-India Muslim League. These differences boiled down to only three pints, namely:

- That the Muslim representation in the Central Legislature should not be less than one-third;

- That in the event of adult suffrage not being granted as proposed in the Nehru Report, the Punjab and Bengal should have seats on a population basis and no more, subject to re-examination after ten years;

- That residuary powers should vest in the provinces and not in the Centre.

The Calcutta Congress in December 1928 resolved that in case the British government did not accept the Nehru Report, which provided that India should have the status of Dominion within a year by the December 31, 1929, the Congress would give up the Report and insist on Independence. The year 1929 saw a great awakening in the country. On October 31, 1929, the Viceroy, Lord Irwin, who had in the meantime visited England for consultation, made an announcement that when the Simon Commission had submitted their Report, the British government would invite representatives of different parties and interests in British Indian and Indian states to meet in a Round Table Conference declared: ‘I am authorized to state clearly that in their judgment it is implicit in the declaration of 1917 that the natural issue of the Indian constitution progress as there contemplated is the attainment of Dominion Status.’

As this part of the declaration left in doubt whether the Conference was to meet to frame a scheme of Dominion Constitution for India, clarification of the point was sought by a Leaders’ Conference which met at Delhi to consider the announcement. Mahatma Gandhi, Pandit Motilal Nehru, VJ Patel, Sir Tej Bahadur Sapru and Mr. Jinnah met the Viceroy on December 23, 1929, on the eve of the Lahore session of the Indian National Congress, in this connection. The Viceroy was not prepared to give the assurance that the purpose of the Conference was to draft a scheme for Dominion Status. The Congress, in pursuance of the Resolution passed at its session in Calcutta, declared that the word ‘Swaraj’ in Article 1 of the Congress Constitution shall mean Complete Independence and that the entire scheme of the Nehru Committee’s Report had lapsed.

Much hard work and heart-searching went into the report. It was not easy to secure a consensus of opinion in a committee whose members diverged widely in their views and aspirations. The committee tried to reconcile the conflicting communal claims and to find a via media between the radicalism of the Congress and the conservatism of the Indian Liberals. The significance of an agreed Constitution was quickly recognized. ‘The day of bondage is ending,’ Mrs. Besant declared, ‘and the dawn of freedom is on the eastern horizon.’ Dr. Ansari recalled the ‘years of utter darkness in which the spectre of communal differences oppressed us like a terrible nightmare’, and was glad that the work of the Nehru Committee had ‘at last heralded the dawn of a brighter day’. ‘It is an achievement,’ Motilal himself said in December 1928, ‘of which any country in the world might well be proud.’

According to BR Nanda, the biographer of Motilal Nehru, “the Nehru report offered not a Constitution but the outline of a Constitution, which could be amplified and put into the form of a bill by a parliamentary draftsman. Among its important recommendations, which were to find their way into the Constitution of independent India, were a declaration of rights, a parliamentary system of government, a bicameral legislature, adult franchise, allocation of subjects between the centre and the provinces, redistribution of provincial boundaries on a linguistic basis, and an independent judiciary with a Supreme Court at its apex.”

As 1928 drew to a close, the Nehru Report was running into difficulties created by the supporters of communal claims. But Motilal was no less worried by the opposition from a radical wing of Congressmen led by Jawaharlal, his son, and Subhash Bose, his devoted follower. Ultimately, Jinnah withdrew his support to the ‘Nehru Report’ as Motilal refused to cross the ‘Lakshman Rekha’ of religion and politics.

Motilal Nehru’s own views on the place of religion in politics were stated bluntly at the Calcutta Congress: “Whatever the higher conception of religion may be, it has in our day-to-day life come to signify bigotry and fanaticism, intolerance and narrow-mindedness... Not content with its reactionary influence on social matters, it has invaded the domain of politics and economics... Its association with politics has been to the good of neither. Religion has been degraded and politics has sunk into the mire. Complete divorce of the one from the other is the only remedy.”

(The writer is a former Secretary AICC)